Martha Jones talks about her book “Vanguard”

Mount Holyoke College welcomes Martha Jones to discuss her book “Vanguard,” how Black women defied both racism and sexism to fight for the right to vote.

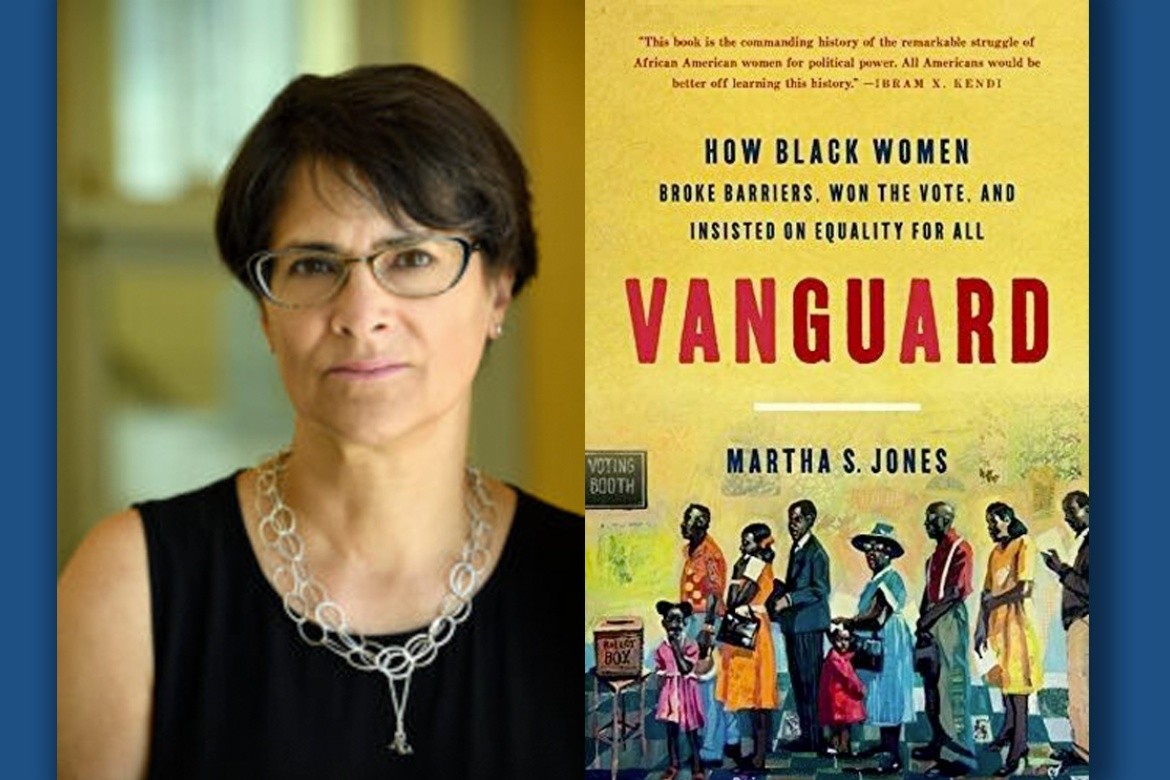

Martha S. Jones, professor of history at Johns Hopkins University, is a scholar, lawyer and historian who focuses on how Black Americans have shaped the history of American democracy. Her new book, “Vanguard: How Black Women Overcame Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All," is a history of Black women's political lives in America.

In the book, Jones recounts how Black women defied both racism and sexism to fight for the ballot, and how they wielded political power to secure equality and dignity for all people. Jones excavates the lives and work of Black women who were the vanguard of women's rights, calling on America to realize its best ideals.

As part of its extended discussion around this year's Common Read, The 1619 Project, Mount Holyoke College welcomes Jones to discuss her work on Thursday, October 29, at 4:30 pm. In advance of her talk, she spoke with the College about her research, her family history and her connection with Mount Holyoke.

The following interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

What spurred you to write “Vanguard”?

I started this book a few years ago. I knew that in 2020 we were going to be marking the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment, and there was a monument being proposed in New York City. It was of the early suffragists in Central Park and the initial proposal included two figures: Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. And that was it. I had the strong sense that we were at risk for having African-American women overlooked in the marketing of the centennial anniversary. So I weighed in on the monument. And to their credit, the planners and designers, after a lot of public commentary, added the figure of Sojourner Truth. And it opened a window for me on what it might be like if more people knew about the contributions and the roles that Black women had played in the movement for women's rights and women's votes.

My way of intervening is to write a book. I'm a historian. I was fortunate because I was able to build on three generations of Black women historians' work, as well as some of my own research, to try and tell a fuller story.

You wove your family history into the narrative. The history of Black women's activism and voting is the history of your family.

Yes, and I am someone who, when I write, I feel very accountable to the women in my family. I didn't really know their stories, it turned out. So I took a kind of detour in the research to see what I couldn learn about them. I discovered some very interesting tidbits. My great-grandmother, who was a suffragist in 1920 in St. Louis, Missouri, was working alongside other Black women to get them to the polls. My grandmother, in the modern civil rights era, was working alongside her students in North Carolina as they did difficult work of voting rights activism on the ground. I think it's important to underscore for readers at Mount Holyoke, is that [I write about] my great-aunt, Francis Harriet Williams, who is a Mount Holyoke alum, class of 1919. She, in her later life, credited Mount Holyoke for her success, and in particular the mentorship of President [Mary] Woolley, who was a great mentor to her.

It's interesting to note that this book comes out at a time when attempted voter suppression is on the rise.

I don't think the story of voting rights in the United States is one of steady, or even inevitable, progress. Voting rights in every generation, it turns out, is a terribly fraught space for thinking and rethinking who has power [and by] by what terms. So here we are. Yes, in the wake of the Shelby County v. Holder decision and the gutting of the Voting Rights Act that ends the book, and now the resurgence of voter suppression exacerbated by the fumbling of public health concerns related to the coronavirus, means that many, many, many Americans and communities of color are very much at risk of missing their opportunity to vote in November.

I think the women in this book would say this is not a moment to sit down. This is not a moment to be discouraged. This is a moment to do the work you need to do, to learn what you need to learn in order to do that work and to link arms with others doing it. Many of the women in the book never lived to see the 1965 Voting Rights Act, but they understood that politics is a long game.

And so here we are, investing in our own moment, in the consequential election of 2020, but we are also investing in the lifeblood of our democracy for ourselves, for our daughters, for our granddaughters — and the women I write about knew that. They knew that in order for this democracy to have any chance, people were going to have to invest in it.