The students making Mount Holyoke more accessible

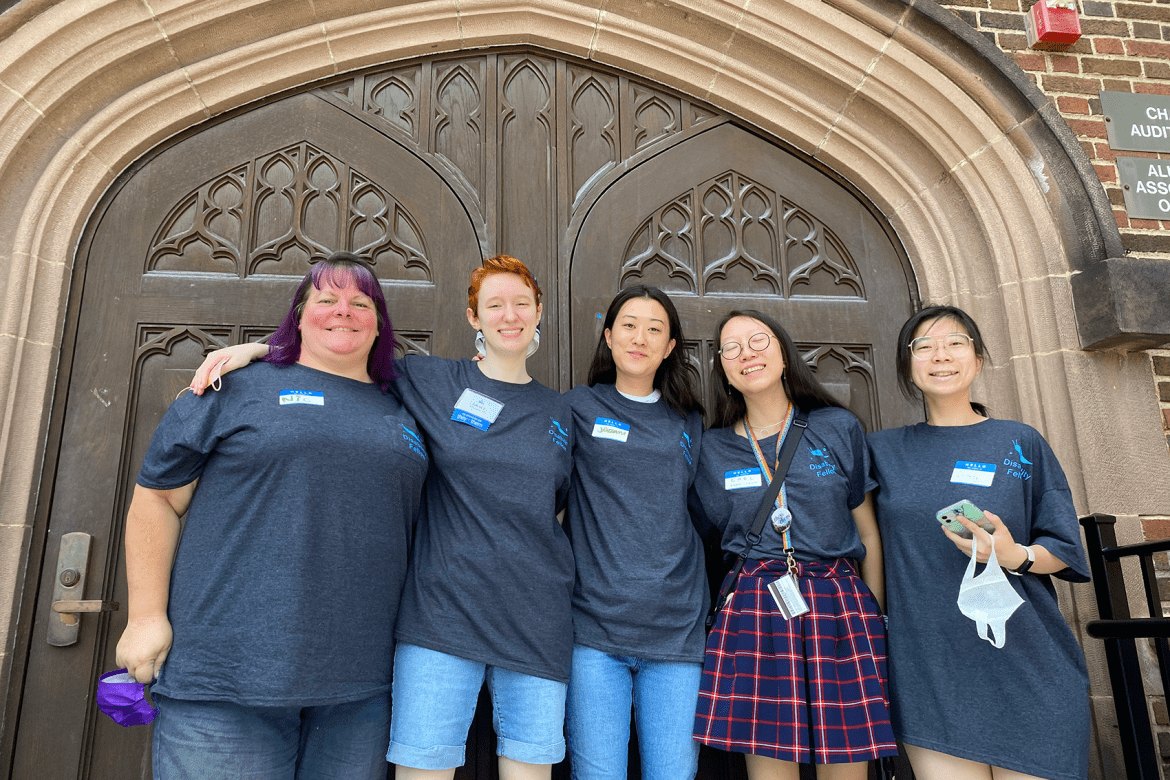

Five Disability Services Fellows are helping facilitate conversations between students and administrators about issues facing Mount Holyoke’s disabled community.

As Mount Holyoke’s accommodations coordinator, Zemora Tevah generally feels well versed in strategies that help neurodiverse students. However, in the fall of 2022, Tevah kept hearing the term “body doubling” mentioned in conversations between Mount Holyoke’s Disability Services Fellows, a group of five students that works with Disability Services. It was a new term for Tevah. And it was proof that the Disability Services Fellows program was working exactly as intended.

“These students have their finger on the pulse of what students are talking about,” said Tevah. In this case, they introduced a helpful new accommodation to Tevah’s repertoire of options.

The Disability Fellows program is a relaunch of an older program called AccessAbility Peer Mentors, said Amber H. Douglas, dean of the College and vice president for student success. That program was an unpaid peer support model. This new iteration is a paid position, with a core group of students taking ownership of advocating on behalf of their disabled peers. The five fellows meet weekly with Disability Services. They are also responsible for planning projects — from special events to staffing tables with literature about how to access accommodations.

“I think that having students in leadership roles benefits the students in those roles and the peers with whom they interact,” said Douglas about one of the benefits of moving this program toward a leadership model.

And because the students are in close contact with administrators, they serve a bridge-like role between the two groups, added Tevah.

Take, for example, body doubling. Body doubling is when two students help each other stay focused by working in tandem — though often on different projects — and observing the other deep in focus. “For ADHD people, working next to another person can increase productivity and focus. We don’t interact at all, but it really helps our productivity,” said Grace MacIntyre ’25, a psychology major from Atlanta, Georgia, and one of this year’s fellows.

MacIntyre became interested in the program due to their work in the disability justice community. For some students, getting a formal diagnosis and the paperwork to be eligible for accommodations is a privilege, they said. But things like body doubling and time management tools can be helpful for students with or without formal diagnoses. MacIntyre hopes to create a series of workshops where students — both neurodiverse and neurotypical — can learn skills for staying organized, managing time and just genuinely thriving in collegiate life.

What Nic McGrath ’24, a gender studies major from Florence, Massachusetts, likes most about being a Disability Services Fellow is that students are more open with her than they might be with administrators. “I get a lot of feedback that I take to Disability Services,” she said. She always tells students that she alone can’t change the system, but she’s happy to bring their concerns to those who can begin to help put change in motion.

Of course, that change can be slow.

MacIntyre and McGrath said that this position has given them an inside look at how complicated change can be. “Some of our buildings are not very accessible. Some of our seating is not very accessible,” said McGrath. Though making those spaces easier for everyone to access is a priority of hers, she also understands why it may not happen overnight.

Likewise, being a Disability Services Fellow showed Joanne Ryu ’23, an American studies major from South Riding, Virginia, just how slammed Diversity Services is. “They are really inundated, and they really are doing the most work on accessibility,” she said. Sometimes, though, students don’t see all that work. She said that having stakeholders working in the office who are members of the student body gives the office another layer of legitimacy.

McGrath dealt with disability services at another university and said Mount Holyoke’s efforts are so much better than most. Still, for some students with disabilities, just walking into an office full of adults can feel overwhelming. McGrath likes that, as a Disability Services Fellow, students often ask her for help first.

“The fellows really extend the reach of our office,” said Tevah. And they’re not just working on helping students access accommodations. “Their work is a little broader,” including engaging in disability advocacy and education outreach, Tevah said.

In the fall of 2023, Disability Fellow Earl Wren ’24, a psychology major, hosted an on-campus seminar titled Augmentative and Alternative Communication 101. As an AAC user, Wren wanted to introduce students to how AAC worked while also highlighting the work and achievements of AAC users. Wren, who has been active in disability justice since before their time at Mount Holyoke, said their focus as a fellow is on advocating for people with lesser-seen and lesser-discussed disabilities. They also hope to introduce the topic of disability justice advocacy to more nondisabled students. “I think even in — or especially in — social justice–oriented spaces, disability often gets ignored and pushed to the sideline,” they said. But fighting for disability justice should be part of all social justice conversations.

One way Disability Fellows are working to bring nondisabled students into discussions about disability and accessibility is by showing films on campus that center disabled artists. The group’s first screening was “The Peanut Butter Falcon,” a 2019 film that starred Zack Gottsagen, an actor with Down syndrome.

While movie nights can help bring disability conversations to a wider campus audience, they can also create spaces for disabled students to connect. “One of my goals as a fellow is to foster a tighter community among disabled people on campus,” said MacIntyre. That’s a goal Wren shares. They added that being disabled can be an isolating experience, and connections are vital for many members of the disabled community.

It’s these connections that often allow disabled students to share what is and isn’t working for them with fellows — and for fellows to pass that information on to administrators. “The people who best understand what students need are students,” said MacIntyre. Sometimes, those needs are things that are already on Disability Services’ radar. However, sometimes — like in the case of body doubling — the information adds an additional strategy.

Ultimately, though, what Tevah likes most about the Diversity Services Fellows program is how visible these students are. “I think one of the best things about this program is that it helps students feel comfortable approaching our office and helps them to know we are not scary and that we want to help support them. We are always trying to reduce as many barriers as we can. To see other students working with us and to say, ‘OK, here are students who are successfully navigating college with disabilities or accommodations’ really helps, I think,” said Tevah.